A CONVERSATION WITH CHIGOZIE OBIOMA

/By Prune Perromat

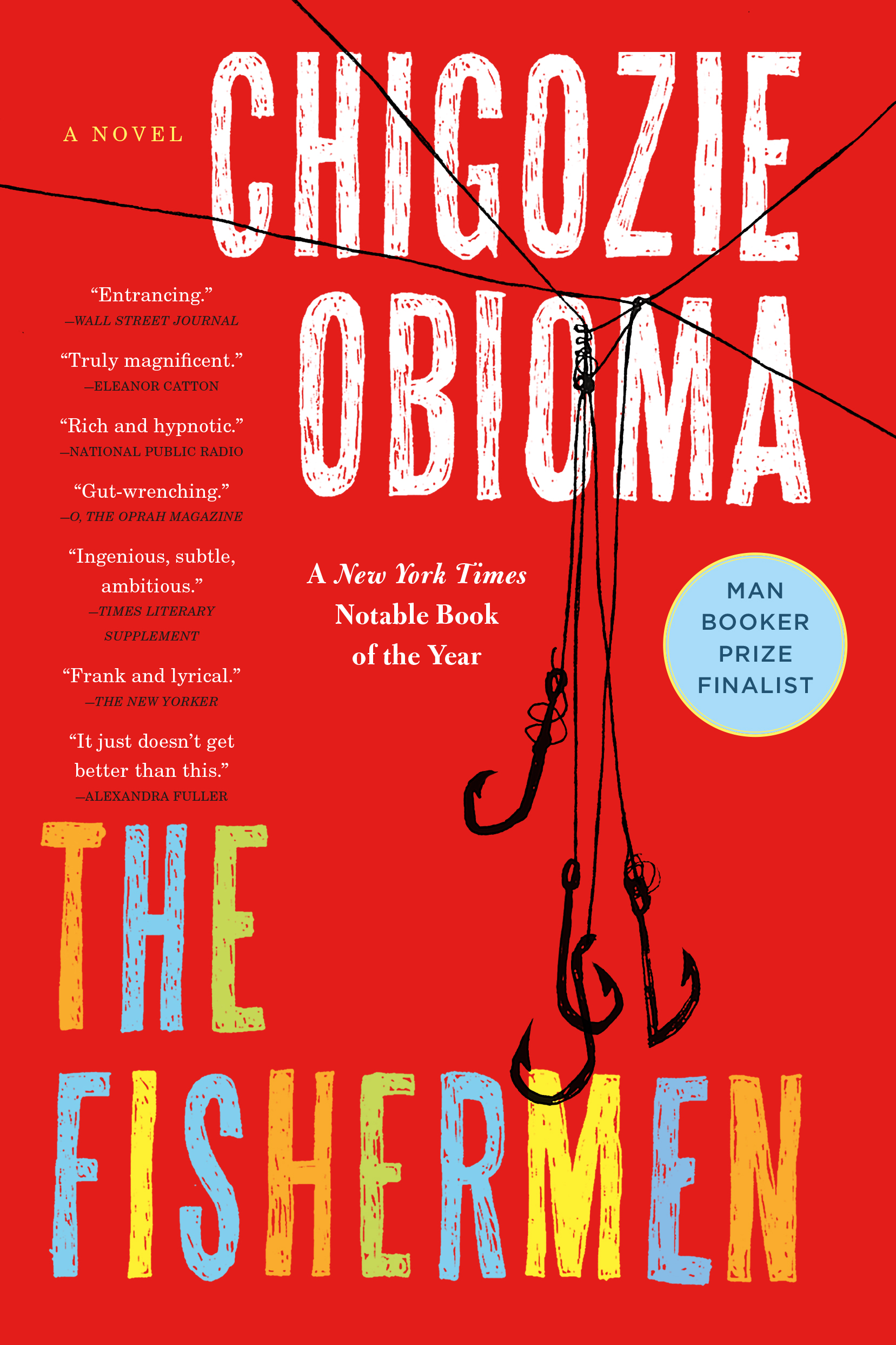

Chigozie Obioma has become an African voice that matters in the literary world. Last year in April -- at only 28 years old -- the Nigerian author published his first novel, The Fishermen (Little, Brown and Company), and swift international acclaim followed. He earned a bounty of literary awards, including being shortlisted for the 2015 Man Booker Prize for Fiction - one of the most prestigious accolades in literature.

Literary critics and readers have been stirred by Obioma's singular storytelling style and incisive prose, which is at times stark, and other times flamboyant. He blends European themes and structure – from the Greek tragedy to Shakespearean drama to 19th century French and British fiction - with an African aesthetic and verve, while also drawing on elements of Latin-American magic realism.

Described as “the heir to Chinua Achebe” – a towering figure in English-speaking African literature who documented the fall of an ancient African civilization in Things Fall Apart – Obioma left Nigeria in his teens to attend university in Cyprus. Far from his family and roots, he was moved to write his first book by an acute and Joycean feeling of nostalgia for his homeland, combined with profound frustration over what he regards as Nigeria’s “failed state" status.

The Fishermen is set in Obioma's hometown of Akure in 1990s Nigeria. It's a Cain and Abel-like story of four brothers whose life is forever shaken by their father’s departure to a faraway town and a subsequent run-in with a local madman. As the brothers grapple with the perils of their newfound freedom and inexorably succumb to the corrosive power of fear, their country also faces its own set of crises in its march to democracy in the wake of independence from the British Empire.

Literary Show Project host Prune Perromat recently met with Obioma in New York ahead of the July release of the paperback edition of the Fishermen. The author is working on his next novel, a love story, that he hopes to complete "by the end of the summer."

* * *

THE LITERARY SHOW PROJECT: The paperback edition of your first novel, The Fishermen, is coming out in July. Since your book was first published, more than a year ago, so much has changed in your life. You’ve been short-listed for the Man Booker Prize and received other prestigious literary awards; the rights for your book have been sold in 27 countries or more, with 22 translations…

CHIGOZIE OBIOMA: This past year has been… very interesting, very life-changing. I didn't expect the attention that The Fishermen got. Initially, we got some rejections from the U.S. But I kind of knew that we had something interesting – but not something that would be short-listed for the Booker Prize or anything like that. That was one of the reasons I rushed to get a job-- right now, I am a professor at the University of Nebraska – partly because I was afraid that the book would be published then and it would just disappear.

LSP: But it didn’t. Far from it. You’re now living the dream of many novelists.

CO: Yes, it surpassed my dream by two million miles. When I was growing up in Nigeria I was always saying I wanted to be a writer. My family was genuinely concerned about it. They’d say: “What are you going to do? How would you make money? Are you going to just end up in penury?” As a child I was kind of successful at school. So they’d say “You are a brilliant boy. Why do you want to waste your life?” I think it is a big sigh of relief that I did not waste my life in the end.

LSP: Let's talk about The Fishermen. When and why did you start writing your first novel?

CO: I left Nigeria in 2007 to go to college in Cyprus, which was a very far place from Nigeria. [For] two years, I hadn't gone back home and it was crazy. I was really homesick. One day my dad and I were talking on the phone and he mentioned two of my oldest brothers, who used to fight a lot when they were kids. But now, they were older and in 2009, they had become very close. So I began to analyze that – the idea of blood relationships, consanguinity, and what makes familial bonds. The moment we had that conversation I think something was deposited in me, in my mind. I almost immediately had this image of a family of four boys. I began to think, what is it that can come between two brothers, separate them, and cause that love to turn into hatred? I came up with fear as the most potent tool. So the novel is the exploration of fear, of what fear can do, what damage it can do to a relationship.

LSP: Even though one narrator alone, Benjamin – the youngest of the four brothers – tells the story there are several levels of narration: one is mature, told by an older Benjamin about two decades after the fact and the other is the fresh and colorful point of view of nine-to-ten year-old Benjamin describing in his own childish way the events unfolding around him. What was your intention here?

CO: We have a belief in Igbo* philosophy that there may be three levels of human characterization: the child, the adult, and the old. Almost no human being is the same during these three stages of life. A man who used to suck his thumb as a child will most probably not continue that habit when he is 25. And the man at 25 who loves to talk dirty may not be drawn to that at habit at 80. My work is often grounded in Igbo or Yoruba** philosophy and science. So what you see [in the novel] is the two levels, which is two different people. The story is told by two people who are also one: Benjamin Agwu, 10, who retells the story at the court and Benjamin Agwu, who tells the story two decades later –‘now that he has sons of [his] own’. I hoped that the two voices would meld together here and there, disintegrate, meld again, disintegrate again as the story is told, until the end. This is also why the novel ends twice.

"I have come to believe that I would not have written The Fishermen if I hadn't moved to the island of Cyprus... My vision of Nigeria became so much sharper merely by looking at it."

LSP: The Python, the Eagle, the Sparrow, the Spiders, the Roosters, the Tadpole… your characters are introduced to the reader as animals. Why do you use those metaphors?

CO: I wanted to let the novel work according to the ways in which the minds of children works when they remember things, and even of adults. They don’t often recall those things in the order in which they happened. But even more so children tend to try to rationalize and understand the world through association with the things they are fascinated by. Benjamin’s is animals. But if your child loves Superman, and they encounter a big man lifting a heavy thing or doing something challenging, they will probably report that they saw a man who was like Superman. That’s what informs the narrative strategy of The Fishermen. Benjamin sees life in comparison to the animal world, which he understands more. When he sees his father leave home to go get food from afar the way eagles do, (…) Benjamin reconciles his father must be an eagle: this, surely, is why he leaves home.

LSP: The boys are torn – just like their country – between their traditional, tribal and African heritage and the lingering influence of colonization, decades after the end of British colonial power. We notice this first in the multitude of languages, but also in their own – very personal – way of embracing the future. Their father has mostly Western dreams for them. But voluntarily or not, they resist and become fishermen, both in the literal and biblical sense of the word. What is this tension about?

CO: While there may be elements of some kind of resistance to the West in the allure of the Omi-Ala river*** the initial impulse to fish there is primal. The boys are driven by the desire to be free from the strict rules of their father and go on what boys their age are often drawn to: adventure. They, I believe, found the river by serendipity. But in a sense, one might argue that the principle of liberté can be reconciled to this mostly primal desire, which then calculates to their reaching for western “principles.” [And] we must recognize that “western civilization” at this point has become ours as Nigerians and that the only difference between the Nigerian and the British is that one: the Nigerian straddles both cultures while the other holds on to only one, mostly.

LSP: I mentioned languages earlier – there are so many in this novel. Within the clan they use English/pidgin English, Yoruba, Igbo. Is this a reality in Nigeria?

CO: Absolutely. Once you are born into a colonial construct like Nigeria you instantly become bilingual, or are at least exposed to more than one language – usually English and the dominant language of the parents. I spoke three, even four, when you include pidgin.

But if I lie down in my bed later that night, and the light was off, and I closed my eyes, the fine-grain details will trickle in."

LSP: The power of memory is absolutely central here. The narrator tells his own story two decades after the events. As an author you have written this novel far from your family and your roots. How powerful can memory be? Could you write fiction about a place you’re currently living in?

CO: The Fishermen was a product of banging an udu, a drum we believe in Igbo land is heard clearer from a distance. I have come to believe that I would not have written The Fishermen if I hadn't moved to the island of Cyprus. The landscape of the country—its serene plains, sparse population, and desolate land—was, to me, so unlike West Africa that it formed such a strong contrast that my vision of Nigeria became so much sharper merely by looking at it. Being away from Nigeria also offered me the ambient space for the story to form.

I have mentioned that the novel was born out of deep nostalgia. If I was back at home, and I saw my siblings every day, the space for the depth of reflection that birthed the story would not have happened. Since the work we do is imaginative, there is much value in trusting the power of hindsight. If I sat across from you at a cafe and I was to describe that moment on the spot, I would write about the obvious things you did. But if I lie down in my bed later that night, and the light was off, and I closed my eyes, the fine-grain details will trickle in. I will remember the unobvious things, the person scratching their wrist, or hawking into a napkin—those fine details that enrich fiction. That is, it is then, when the person is gone and the meeting is ended and the day is forgotten that things become closer, clearer.

A 1993 poster of Nigerian presidential candidate "Chief" MKO Abiola a key political figure in Obioma's The Fishermen, long thought of as a symbol of Nigeria's democratic aspirations

LSP: Your prose is very stark, precise. But there's a kind of fire beneath the words that come from emotion – the expression of subjectivity. Is that something you felt when writing?

CO: Yes. Although the novel was inspired by my homesickness it was also driven and sustained by fury, some kind of anger. It has a biblical aspect. It also has a political aspect to it. I wanted to talk about how West Africans – where the boys are from – had their own political system that was democratic, superior to the British monarchical system of the 19th century or 18th century; had their own religion; had everything that was unique in its own way, uniquely African. But the Western people came and said, ‘this is inferior, this is barbarian,’ and imposed their own way of life. And this is what the madman [Abulu] does to the boys. They are happy people at the beginning of the novel. They all had dreams. Ikenna wanted to be a lawyer, Boja wanted to be a doctor... and then the madman intrudes. We are still struggling as a nation because our lives were transformed by an imposition from an external force. Although Nigeria is a very rich country, we don’t have this constant electricity, wireless. Cyprus, which was a desert, is a desert, has these things, this infrastructure. So I was angry. I was thinking about the reasons why we have failed to achieve this level of promise.

LSP: What do you think of the state of Nigeria now?

CO: I think it's a failed state. The reason why I say that is most people would disagree and [argue] that it has not failed because it's still running. But relative to the resources… Nigeria is the [12th] largest oil producer in the world, the [7th] most populous nation in the world, and one of the most educated with a high literacy level. Yet you go to Nigeria [and] it's not normal to have electricity 24 hours a day. To me, that is a failure.

LSP: You’ve said before that for a work of fiction to be successful you need three things: having something to say; a plot, an arc that can be told orally; and a philosophical framework. Is it a rule you try to follow in all of your fiction writing?

CO: Yes, indeed. I think some people are writing without a “definite something to say,” driven just because of the need to be a writer, or money, or fame. This is a tragic thing. Yes, I love conceptual novels, but then a work of fiction is at first an exercise in storytelling. When concept trumps plot, perhaps a piece of fiction can work. But when it erases plot entirely then I think the writer may have failed. This is why Vladimir Nabokov has succeeded greatly.

Obioma, age 11 or 12, receiving the award for best literature student at his primary school in 1998.

LSP: There seems to be so many literary influences in your book, from Greek mythology, to Shakespearian drama, to 19th century European novels à la Dickens or Zola, to a sharp style that reminds some of Cormac McCarthy, with a touch of Gabriel García Márquez. You’re obviously a voracious reader. How early did you start reading?

CO: When I was about eight or nine, I was always down with malaria or something, and frequently spent several days in the hospital. During those days my dad would sit by my bedside and tell me stories. Then one day, healthy and at home, I asked him to tell me a story, and he said, ‘Go and read it yourself.’ He gave me a book and I read it and discovered that one of the most fascinating stories he’d ever told me was in that book! It was Amos Tutuola’s mythic odyssey, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, which also happens to be the first black African novel in the English language. That was a pivotal moment. Prior to that I had always seen my dad as this great man who had this vast reserve of stories. But then I saw I could actually get this thing from books and I started reading voraciously. And then I began to replicate the stories in written form, so that was the point where I moved from a storyteller to a writer. Going forward I read everything that was in my father’s library, and oh boy – the man trafficked in Greek and Shakespearean tragedies and in the works of Amos Tutuola and [Chinua] Achebe and the rest of them. I did not read McCarthy till The Road in 2011 and have never read [Theodore] Dreiser. So it is interesting that my work is being likened to theirs.

LSP: You’ve indeed been compared to many great writers, including the great Nigerian author Achebe, whom you just mentioned. How do you think your work relates to his?

CO: In some ways, (my book) shares affinity with Things Fall Apart, Achebe's seminal work. Achebe wrote Things Fall Apart to document the fall of the Igbo civilization, the African civilization or culture. I am looking at a more specific fall of Nigeria – of our civilization too but in relation to Nigeria specifically. So it's a similar project.

LSP: You’ve started working on your new novel, The Falconer, before the publication of The Fishermen and you’re still in the midst of the creation process as we speak. What kind of pressure is there on an author who is writing a new book after his previous work has been so widely praised?

CO: I am lucky that I already had something in place before all of this happened. The way that the publishing industry works is that if you signed a book deal say, now, it takes –mostly – at least a year and a half for a book to come out. Mine took almost two years. Within that time I had started working on another book. I am not trying to change anything or to force anything. I just want to do it. I could decide to publish it in ten years from now. I think the book has been wanting to come out for a long time. So it's time.

LSP: Will the action take place in Nigeria?

CO: Mostly, yes. But it does leave Nigeria. It goes to Cyprus as well. In some ways it is more joyful I think. It’s a love story. I mean, this too – The Fishermen – is a love story: what drives the book is the relationship between the brothers, a sibling love actually. But in the new book it's a self-sacrificial love. This guy gives up all he has for the woman he loves and pays dearly for it and tries to reconcile his sacrifice to his life. I look forward to sharing it. I hope to complete it by the end of the summer.

* Chigozie Obioma’s ethnic and cultural group, predominant in southeastern Nigeri // ** Major ethnic group in southwestern Nigeria, where the town of Akure is located // ***The imaginary polluted and forbidden watercourse running through the boys’ town.

The Fishermen is published by Little, Brown and Company. It was first released in hardcover in April 2015. The paperback edition was published in July 2016.