Beyond the Arab Spring, the Fight for Freedom in the Digital Age

/Celebrations in Tahrir Square after Omar Suleiman's statement concerning Hosni Mubarak's resignation. Photo: Jonathan Rashad via Flickr

Six years ago, on January 25, thousands of people descended on Tahir Square in Cairo for a protest that would eventually topple the government and escalate the Arab Spring. On the anniversary of that climacteric demonstration, and in the wake of historic, global women's marches, we take a look at two works that offer some of the past year’s best insights into dictatorship and protest.

BY EMILY LEVER

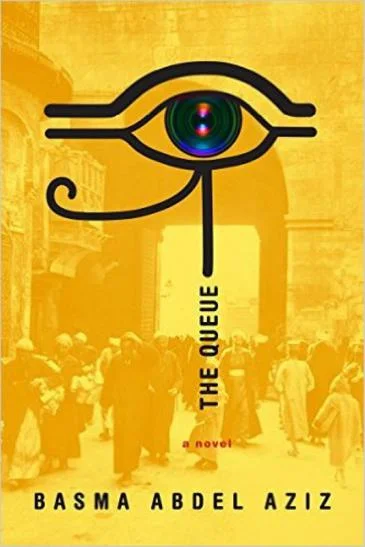

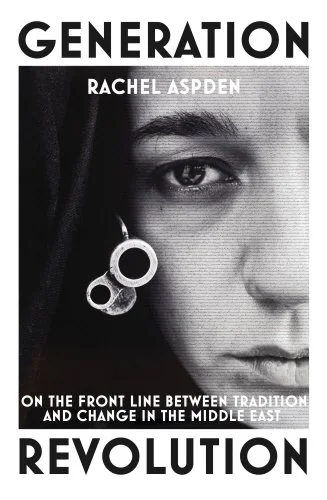

Two rather different books, The Queue and Generation Revolution, offer us complementary portraits of the same society, one where some young people agitate as fiercely for progressivism as others do for conservative values; where social media has sparked a powerful protest movement; where fierce debates about freedom, religion, and freedom of religion rage. I am speaking, of course, of Egypt. As 2017 begins, these two works offer some of the past year’s best insights into dictatorship and protest.

Rachel Aspden’s Generation Revolution profiles a number of young Egyptians, from a financially independent single woman to a Salafi activist to a Quran reciter turned atheist. Aspden weaves some dozen perspectives into an account of the Arab Spring and what followed: the ouster of Hosni Mubarak, the hope-filled tenure of Mohammed Morsi, and the return to repression under Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz, a psychiatrist who treats torture victims, is a dystopian satire set in a thinly veiled post-Arab Spring Egypt. In the tradition of Wole Soyinka’s Kongi’s Harvest, which skewers the pettiness of dictators, or Olga Grushin’s The Line, it’s a novel about how the most minute, vital things can be taken hostage by autocrats. In the titular queue, citizens await government authorization for simple things they desperately need. For one man, Yehya, it’s surgery to extract a police bullet from his stomach. He and his loved ones go through absurd bureaucratic processes--like applying for a “Certificate of True Citizenship,” which is required to successfully complete any bureaucratic process--to get Yehya surgery before he dies, while a sympathetic doctor contemplates the risks of helping him.

Though Generation Revolution is a helpful primer for those who might not otherwise catch Abdel Aziz’s allusions to current events in Egypt, I found The Queue a more compelling read. This may reflect the fact that Abdel Aziz is Egyptian and Aspden is not: distractingly, Aspden spends too many paragraphs dithering about aspects of Egyptian culture that clash with Western sensibilities. Abdel Aziz simply tells her story, peppering it with sharp social critique--without the burden of incomplete knowledge or the self-appointed responsibility of the Western observer to pass judgment. Aspden’s book is at its best when she delivers empathetic but pointed insight into her subjects. Of a socially conservative young man frustrated at how much he’s expected to spend on his wedding, she says, “The problem of money made Abdel Rahman...for the first time, dissatisfied with tradition--now he felt he was on the wrong end of it.”

To a reader in America in 2017, both books will provide illuminating lessons about political rebellion: it’s not glorious or instantly successful, but doing nothing is worse. The fictional and real Egyptians in these books feel worst when they have the opportunity to make a difference but don’t take it. They know that to opt out of the fight would be to dodge their responsibility to their communities and themselves.

These people live in societies so tightly controlled that deviation seems impossible. Even to the disaffected, the status quo can seem so inevitable that envisioning a different world feels as difficult as imagining the earth is flat. But for a time, the people profiled in Generation Revolution managed to do just that. Though the progress gained through protest has been rolled back, one hopes Aspden is right in supposing that a people who has experienced freedom will not suffer tyrants for long. LSP